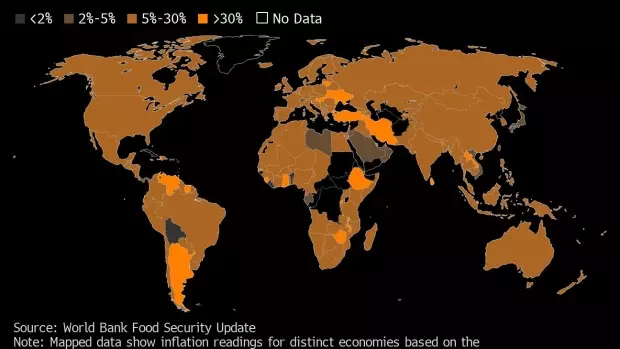

London October 16 2022: Food importers from Africa to Asia are scrambling for dollars to pay their bills as a surge in the US currency drives prices even higher for countries already facing a historic global food crisis.

In Ghana, importers are warning about shortages in the run up to Christmas. Thousands of containers loaded with food recently piled up at ports in Pakistan, while private bakers in Egypt raised bread prices after some flour mills ran out of wheat because it was stranded at customs.

Around the world, countries that rely on food imports are grappling with a destructive combination of high interest rates, a soaring dollar and elevated commodity prices, eroding their power to pay for goods that are typically priced in the greenback. Dwindling foreign-currency reserves in many cases has reduced access to dollars, and banks are slow in releasing payments.

“They cannot afford it, they cannot pay for these commodities,” said Alex Sanfeliu, world trading head for crop giant Cargill Inc. “It’s happening in many parts of the world.”

The problem isn’t a new one for many of the countries — nor is it limited to agricultural commodities — but the reduced purchasing power and dollar shortages are compounding wider strains across global food systems following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The International Monetary Fund has warned of a catastrophe at least as severe as the food emergency in 2007-08, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called for more food aid for the most vulnerable, while the World Food Programme says the globe is facing its largest food crisis in modern history.

On the ground, many importers are struggling with rising costs, shrinking capital and difficulty in obtaining dollars to ensure their shipments are released from customs on time. That means cargoes get stuck at ports or may even be diverted to other destinations.

“There was always a historical strain on making these payments, but at the moment it’s unbearable pressure,” said Tedd George, a consultant specializing in Africa and commodities markets.

In Ghana, where the cedi has lost about 44% this year against the dollar — making it the second-worst-performing currency in the world — there are already worries about supplies ahead of Christmas.

“We think there is going to be a shortage of some food items,” said Samson Asaki Awingobit, executive secretary of Ghana’s importers and exporters association which includes buyers of grains, flour and rice. “The dollar is swallowing our cedi and we are in a hopeless situation.”

To be sure, some countries may be cushioned by their purchases in other currencies like euros, while energy-exporting nations will profit from overseas revenues. Global food-commodity costs have also fallen for six straight months, giving hopes for a relief to consumers.

But the soaring dollar threatens to erode some of that benefit, according to Monika Tothova, an economist at the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, which sees this year’s global food import bill at a record high.

The situation is still fragile. Concerns are mounting anew over supplies out of the Black Sea region as the war in Ukraine escalates and there are questions over the future of the deal to ship grains out of Ukrainian ports. Weather shocks have driven volatility in recent months, stocks are low and soaring fertilizer and energy prices are boosting food production costs.

As the Federal Reserve continues to tighten monetary policy, the dollar’s strength versus currencies in emerging and developing markets will add to inflation and debt pressures, the IMF said in its global outlook this week.

In flood-ravaged Pakistan, government moves to prevent foreign-exchange outflows meant that containers holding food like chickpeas and other pulses piled up at ports last month, sending prices surging, according to Muzzammil Rauf Chappal, the chairman of the Cereal Association of Pakistan.

The situation eased after the appointment of new finance minister who pledged to clear pending transactions for businesses that have been delayed because of a dollar shortage in its interbank market.

“The situation was quite dangerous,” said Chappal, whose company is the country’s biggest private sector wheat importer. “We were expecting the country to face a serious grain crisis.”

In Egypt, one of the world’s top wheat importers, shortages have plagued private sector mills that supply flour for bread that isn’t part of the country’s subsidy program.

About 80% of millers have run out of wheat and stopped operations as some 700,000 tons of grain remain stuck at the country’s ports since the start of last month, according to the Chamber of Cereal Industry. The supply ministry said Wednesday it would provide wheat and flour to private sector mills and pasta factories.

Cargill’s Sanfeliu said he expects global wheat trade flow to shrink by as much as 6% in the upcoming months, with corn and soybean meal flows dropping by as much as 3%, as developing countries struggle to pay for food and animal feed.

In Bangladesh, business conglomerate Meghna Group of Industries may have to cut the amount of wheat it had planned to import before the war broke out amid at least a 20% jump in wheat import costs due to the stronger dollar, said Taslim Shahriar, the company’s procurement official.

“Currency fluctuations are creating huge losses for the company,” said Shahriar. “We have never seen this before.”