Riyadh May 30 2023: Oil giant Saudi Aramco shares a couple of traits with Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corp.: a market capitalization measured in the trillions of dollars, and a stratospheric price-to-earnings ratio. Unlike those tech behemoths, though, Aramco’s valuation relies more on smoke and mirrors than the market’s collective wisdom.

That matters because the Saudi government, which directly and indirectly still controls 98% of the company’s equity after its 2019 initial public offering, is now mulling whether to sell more shares.

Technically, there’s nothing unreasonable about Aramco’s valuation, currently sitting just above $2 trillion and making it the world’s third-largest publicly traded company. After all, willing buyers and sellers set the price transparently on the stock market. That’s how companies are valued in a capitalist system.

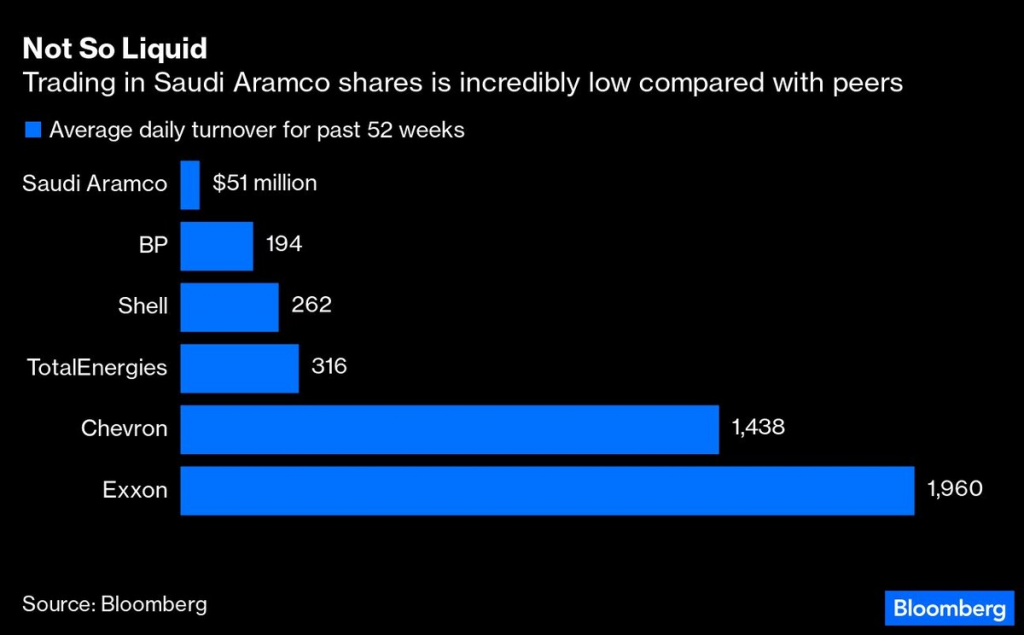

The problem is the quality and breadth of that price discovery. The liquidity in Aramco shares is abysmal: a daily average of just $51 million worth of stock changed hands over the past year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Compare that with nearly $2 billion for Exxon Mobil Corp. For Apple and Microsoft, the figures are $11.2 billion and $7.5 billion, respectively.

It isn’t just that liquidity in Aramco is low — with just 2% of the shares available for trade, that’s not such a surprise — it’s also troublesome that many buyers and sellers are involved in what looks like merry-go-rounds. Middle East investors, often controlled by regional governments or royals, trade with each other, back and forth. The big institutional investors are absent. And don’t waste your time looking for short sellers: they don’t exist.

By selling more shares, the Saudi government may improve liquidity. For that, however, investors need to actually trade the stock. Since the 2019 IPO, many investors have treated it as a buy-and-hold investment, akin to a perpetual bond.

Aramco executives are aware of the problem. “We recognize that average traded volume compared to a stock of our size is not high,” Ziad Al-Murshed, the company’s chief financial officer, told investors in a conference call earlier this month. “A lot of this is not under the direct control of the company. A lot of the shareholders are holding the shares, and therefore the traded volume is not too high.”

Recognizing a problem is the first step toward solving it. But what to do? A new market-making mechanism, introduced by the Saudi stock exchange, may help at the margins. The only real solution, however, is to attract interest from the large pool of overseas capital that buys and sells oil stocks in places like London, Hong Kong and New York. That, however, isn’t practical at the current stratospheric valuation.

Put simply, Aramco isn’t worth that much for sophisticated international investors. That’s why most of them skipped the 2019 IPO at an even lower valuation, and is why they are likely to pass once more if Riyadh goes ahead with its plan.

In an e-mailed response to questions, Aramco said that low liquidity isn’t deterring investors. “On the contrary, we believe there is strong appetite for what Aramco has to offer,” it said, adding it provided investors with “unrivalled profitability, cash flow and returns.”

Aramco trades at a price-to-earnings ratio of 13.5 times, nearly double that of Exxon. In mid-2021, the ratio peaked at nearly 40 times. Those are numbers more appropriate for shoot-for-the-moon tech stocks, not an old-fashioned oil company. The other consequence of an elevated P/E ratio is a low dividend yield. At its current valuation, Aramco offers just 3.8%, compared with nearly 4.5% for BP Plc.

Moreover, investors can get a yield of as much as 4.6% by buying two-year Saudi government debt denominated in dollars, and 5.5% on the sovereign’s bond repayable in 30 years. Shares rank below debt in any capital structure; why would a foreign investor accept a lower yield on riskier Saudi exposure?

The Saudi government is trying to attract more investors for Aramco by juicing dividends. Buybacks, the preferred route for Big Oil to return capital to shareholders, aren’t an option for Riyadh, because they would further reduce the stock’s free float. With profits surging and cash at hand, Aramco earlier this month promised to top up its regular dividend with a so-called “performance” dividend, equal to 50% to 70% of its annual free cash flow, net of the base dividend and other expenses.

The extra cash would boost the dividend yield — or so Aramco hopes. Still, it’s unlikely to convince overseas money. Foreign investors have better options, starting with the country’s hard currency sovereign debt. If an overseas portfolio manager wants to speculate on a combination of the oil economy and Saudi political risk, those government bonds are a more lucrative — and safer — investment than the national oil company.