RIYADH/DUBAI, January 10 2024 – For private equity investor Imad Ghandour changes in Saudi Arabia’s laws are prompting a rethink and his firm may buy, for the first time, minority stakes in the kingdom’s companies. It is exactly an effect the country’s leaders are aiming for as they seek to woo billions of dollars in new capital to wean its economy off fossil fuels.

On Dec. 16, the kingdom’s first written civil code came into effect, replacing a system where judges would have full discretion in ruling on commercial disputes using Islamic law, sharia, as guidance. That created uncertainty for investors like Ghandour, who until now would only invest in majority stakes in Saudi companies.

The new framework “allows us to protect ourselves better and more predictably than under the old law,” said Ghandour, co-founder and managing director at CedarBridge Capital Partners, which has over $140 million in assets in Europe and Middle East.

The new civil transactions law is part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 reform plan to pivot its economy away from oil and gas sector.

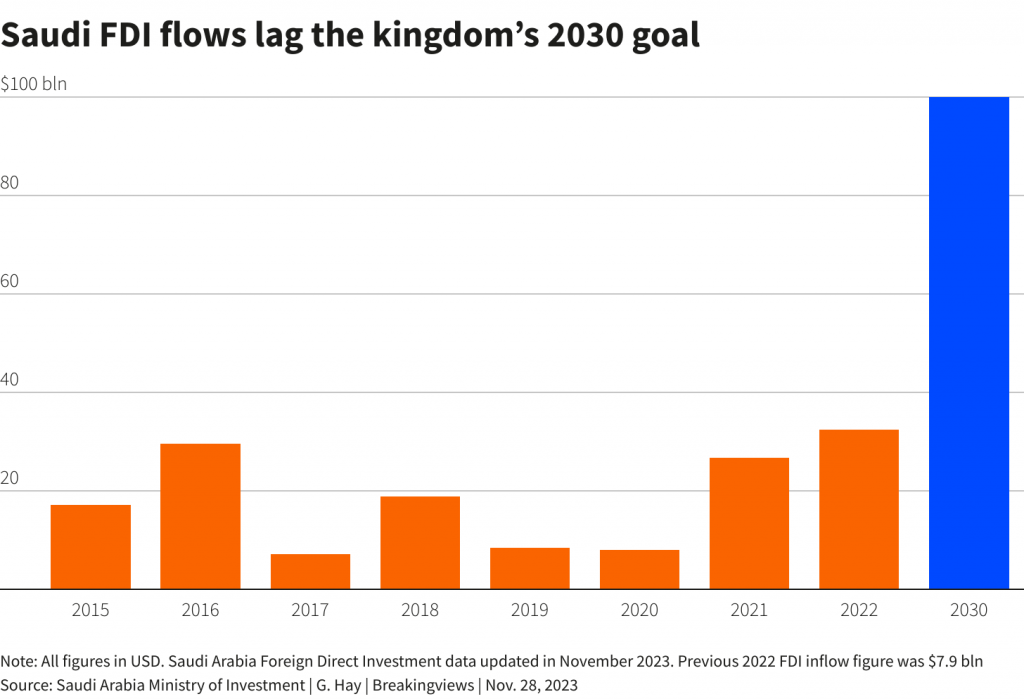

Riyadh in 2021 set target of reaching $100 billion in foreign direct investment by 2030, which appears still far off with most recent data showing just under $33 billion in inflows in 2022.

Some advisers say the new law could be a game changer – providing legal clarity for the legions of banks, law firms, asset managers and corporations that are establishing offices or weighing investments in the Gulf’s biggest economy.

“The very existence of a code, which states succinctly and clearly what the legal position is vis-à-vis certain issues be it contract formation, damages, termination, or otherwise, will give much more confidence to investors,” said Joseph Chedrawe, a partner at law firm Covington & Burling, who advises companies involved in international disputes in the country.

DOUBTS

Lawyers, bankers and investors interviewed by Reuters point out, however, that uncertainty about how the new laws might be applied means it could take time before more deals materialised, leading to a visible pickup in direct investment inflows.

“You need to then see it applied and to see the courts apply it, that’s going to be a road of discovery for the judges to a degree,” said Andrew Mackenzie, head of litigation, arbitration and investigations for Middle East at DLA Piper, who advises businesses in Saudi Arabia.

Ghandour also said his firm would need to see how the law works in practice before making any firm commitments.

But at least the legal framework should no longer act as a deterrent.

“For a lot of business leaders, the political risk of operating in Saudi Arabia was too high,” said Jim Krane, research fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute in Houston, about the past lack of written business code and discretionary rulings.

While the new law still broadly follows sharia principles, it is based on the Egypt’s 1849 civil law modelled after the Napoleonic Code and sets legal guidelines judges have to abide by. Judges are receiving training in the new law and the law will apply retroactively to all contracts, said Chedrawe.

Ghandour said the new code now allows shareholder deals to include a right to exit an investment through a pre-agreed clause or the ability to force minority shareholders to join the sale of a company. Previously such rights were not universally enforced and made investor positions weaker, said Ghandour.

Also, in the past, when parties sought damages in litigation, courts could adjust the amounts depending on judges rulings. Under the new code any damages will be limited to what is listed in the contract except in cases of fraud or gross negligence.

More clarity also means banks will probably need to set aside less capital when making collateralised loans, which could free up more funding, said one financier.

A contractor can also stop work if they do not receive payment, or if the contract is otherwise breached.

The new law also allows to sue for loss of profit, previously a legal grey area, because sharia guidance generally stated that compensation had to be a fixed amount.

Still, there are lingering doubts how foreign and local parties would be treated in cases of business disputes.

One global investor, speaking on condition of anonymity because the matters were private, said they turned down an investment in the kingdom because it would have been under Saudi law. The investment group still preferred deals in countries where they could be structured in a way that they are governed by European laws.

Many investors still prefer to draft contracts using British law with a clause for arbitration to avoid Saudi courts, said a lawyer with a U.S. law firm, who also spoke on condition of anonymity.

These investors want to avoid potential litigation in Saudi courts, which they believe may side with the government rather than a foreign investor, said the lawyer.