Washington DC October 23 2024: In countries where inflation is very close, or at target, policymakers should show openness to easing faster, if evidence suggests inflation may end up undershooting the target for a while, suggest IMF.

In countries where inflation remains stubbornly above targets, central banks should push back against overly optimistic investor expectations for monetary policy easing.

When it comes to financial stability, the world is facing a split screen of short-term and medium-term factors. The good news is that near-term financial stability risks remain contained.

Why? Because the likelihood of a soft landing for the global economy has significantly increased. As inflation continues to decline, major central banks have started cutting interest rates. This is boosting already buoyant asset prices and keeping financial market volatility subdued.

At the same time, IMF latest Global Financial Stability Report calls on policymakers to remain vigilant about the medium-term prospects. We want to highlight two areas of concern.

Concerns down the road

For one, accommodative financial conditions have continued to increase vulnerabilities, such as lofty asset valuations around the world, increased government and private-sector debt levels, and more use of leverage by financial institutions, to name a few. All this could amplify future shocks to financial systems. We have seen vulnerabilities mount before, most notably ahead of the 2008 global financial crisis. The build-up is usually gradual, which should give policymakers time to adjust.

The second area of concern is the disconnect between heightened uncertainty—especially related to increased geopolitical risks—and financial market volatility. A standardized measure of volatility has drifted far below geopolitical risk measures. This indicates that asset prices may not fully reflect the potential impact of wars and trade disputes. Such a disconnect makes shocks more likely, because high geopolitical tension could trigger sudden sell-offs in financial markets and prompt volatility to snap back as it catches up to uncertainty. In that case, some financial institutions may be forced to sell assets or deleverage balance sheets to meet margin calls or satisfy risk limits. While such actions may protect individual institutions, they can actually exacerbate market sell-offs.

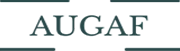

The market turmoil in early August, while not a geopolitical event, still provides a glimpse into such a scenario. The narrowing of US-Japan interest rate differentials following a rate hike by Bank of Japan in late July and a soft US payrolls report in early August led to a strengthening of the yen-dollar exchange rate. This, in turn, precipitated the unwinding of leveraged yen carry trades and spurred sell-offs in stock markets. While US stock indexes declined significantly, Japan’s benchmark Nikkei index dropped by 12 percent, its largest single-day move since 1987.

Other factors also exacerbated the sell-off: investors started to buy equity put options to protect against losses, driving up stock volatility especially in Japan and the United States. Meanwhile, the volatility spikes triggered risk limits for some investors like hedge funds and momentum traders, leading to further sell-offs. To be sure, market pressures proved to be temporary and did not threaten financial stability. But the sharp move by investors toward risk avoidance clearly showed how shifting sentiments can quickly amplify volatility.

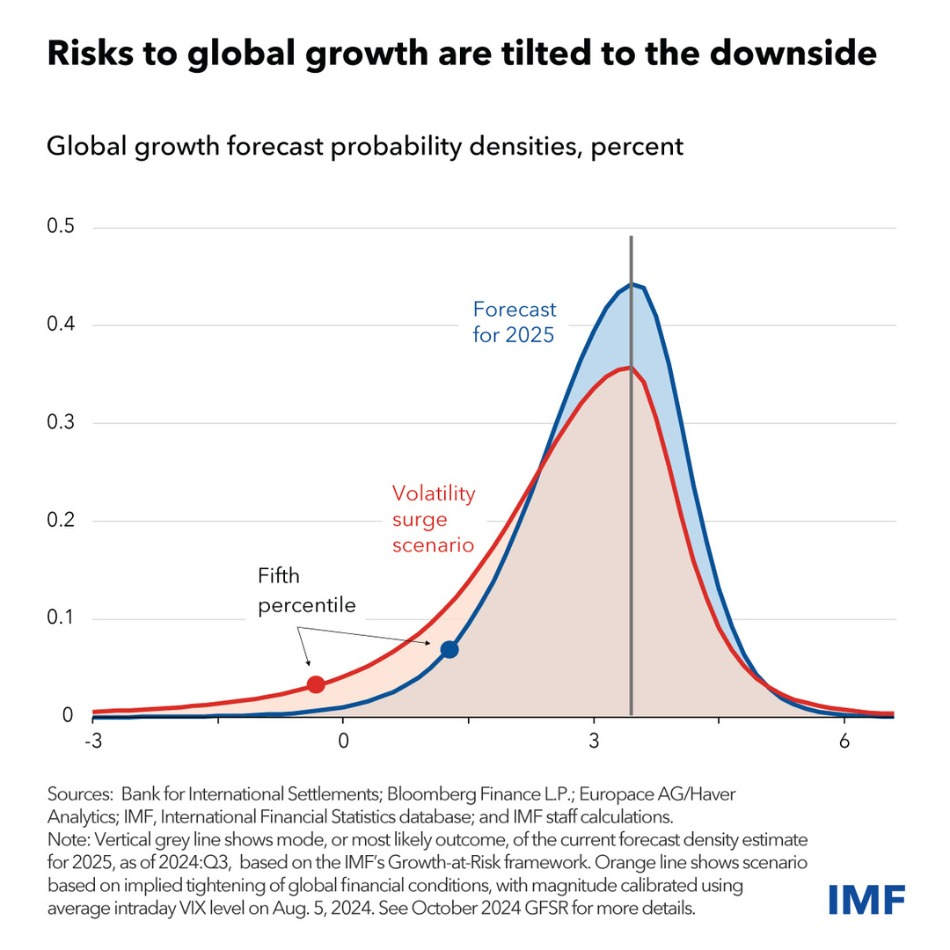

Another key variable for financial policymakers is the economic outlook. The IMF’s Growth-at-Risk framework links current financial conditions to the distribution of possible outcomes for future growth and sums up our current financial stability assessment. Near-term risks to growth appear contained at moderate levels: the probability of global growth falling below the World Economic Outlook baseline for 2025 is estimated to be around 58 percent. And tail outcomes are not too severe owing to financial conditions having remained accommodative alongside healthy credit growth.

And yet, policymakers need to be vigilant. Given the large disconnect between uncertainty, geopolitical risk, and financial market volatility, surges in volatility would likely be more prevalent. In a scenario where financial conditions tighten akin to what we saw on August 5—and remain at that level for an entire quarter—the probability of 2025 growth falling below the WEO baseline increases to around 75 percent, comparable to the peak of the COVID crisis, suggesting that downside risks could rise materially when volatility catches up to uncertainty.

Time to act

In short, as the global economy continues to grow, and with monetary policy easing, risk-taking by investors could increase. And thus, vulnerabilities such as debt and leverage could build up, raising downside risks in the future.

So, what can policymakers do now?

In countries where inflation remains stubbornly above targets, central banks should push back against overly optimistic investor expectations for monetary policy easing. Where inflation is very close, or at target, policymakers should show openness to easing faster, if evidence suggests inflation may end up undershooting the target for a while.

On the fiscal side, adjustments should focus primarily on credibly rebuilding buffers to keep financing costs at reasonable levels, as shown in the IMF’s latest Fiscal Monitor.

We also need more progress on financial policies. Fragilities created by nonbanks using more leverage and maturity mismatches underscore the need for more active regulatory and supervisory engagement. This includes implementing the Financial Stability Board’s agreed-upon standards, the strengthening of macroprudential policy frameworks to contain excessive risk taking, and the additional collection of data to enhance transparency for market participants and policy makers alike. Furthermore, it should be ensured that central counterparties—increasingly used to clear financial transactions— remain resilient; for instance, by having sufficient liquidity to cover potential losses that may arise during periods of market stress.

Now is the time for policymakers to keep a close eye on the second screen: while achieving an economic soft landing remains critical, we need to step up proactive measures to prevent future fragilities.