Accra March 1 2023: Ghana’s eurobonds sank to the lowest level in nearly three months after the country missed a self-imposed deadline to restructure its bilateral debt and S&P Global Ratings warned that bondholders face larger losses than anticipated.

Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta wanted to reach a restructuring agreement with bilateral creditors by the end of February to help qualify for a $3 billion International Monetary Fund program. So far, Ghana has only partially completed the domestic-debt part of the exchange plan.

Meanwhile, S&P said private creditors may have to write off as much as 50% of their debt holdings — far higher than the 30% haircut the government initially suggested. The country’s 2032 dollar bonds slumped to 36.69 cents on the dollar on Wednesday, the least since Jan. 5. They traded near 39 cents as recently as two weeks ago.

The missed deadline doesn’t automatically derail the restructuring talks. Rather, it highlights the difficulties Ghana faces as it tries to reduce its debt load and contend with critics ranging from international bondholders to local trade unions.

“In the presence of a sizable exchange-rate shock, which Ghana has clearly experienced, the haircut tends to be higher,” Frank Gill, S&P’s sovereign specialist for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, said in an interview. “Moreover, historically, the longer the duration of debt restructuring talks with creditors, the higher the haircut has ultimately been.”

A spokesperson for the finance ministry didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment on the government’s plan after the deadline expired.

Fragile Cedi

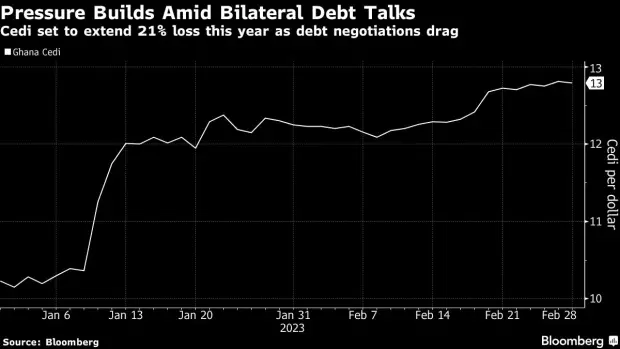

The impasse is also stoking volatility in the cedi, which has slumped 20% against the dollar in 2023, the worst performer among more than 100 currencies tracked by Bloomberg after the Lebanese pound.

“For the foreseeable, future the cedi will continue to be volatile until we are able to make substantial progress on the external debt restructuring front,” said Kweku Arkoh-Koomson, an economist at Databank Group. “The IMF deal is what will cause a clear stability in the cedi.”

Ghana is trying to restructure most of its public debt, estimated at 576 billion cedis ($45 billion) at the end of November. Local bondholders have been asked to voluntarily exchange 130 billion cedis of debt for new bonds that will pay between 8.35% and 15% interest, compared with an average of 19% on old bonds.

“Uncertainty on when the rest of the restructuring will be completed” is influencing cedi volatility, said Courage Boti, an economist at Accra-based GCB Capital Ltd. “To the extent that those things are hanging in the balance now — in that timelines are not very certain — the volatility of the cedi will continue.”

To date, local investors have exchanged 87.8 billion cedis, or 67.5% of bonds under restructuring, for new securities, against an overall target of 80%. The country will have to reorganize obligations owed to local pension funds to complete the domestic exchange, a move that’s running into criticism from trade unions.

A committee is still working on how “to bring on board the pension funds without suffering any principal or interest losses,” Thomas Esso, executive secretary of the Chamber of Corporate Trustees, an umbrella body for the private pensions industry, said Wednesday by phone. “Until their work is completed, the government will continue to pay the old bonds when they fall due.”

The government aims to start “substantive” discussions with international bondholders and their advisers in coming weeks, Ofori-Atta said last month, offering eurobond holders some losses while seeking to reschedule payments on bilateral obligations.

The nation’s foreign debt is rated in default by S&P. Earlier this month, Fitch Ratings withdrew coverage of all Ghana’s unsecured foreign bonds and cut the country’s credit score to partial default after it missed a eurobond coupon payment and a 30-day grace period expired.