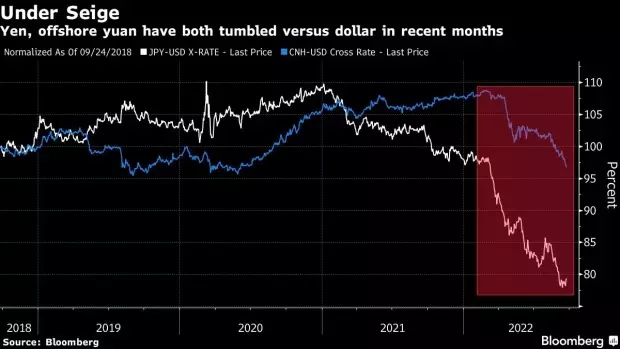

London September 26 2022: Asian markets risk a reprise of financial crisis-level stress as two of the region’s most important currencies crumble under the onslaught of relentless dollar strength.

The yen and yuan are both tumbling due to the growing disparity between an uber-hawkish Federal Reserve and dovish policy makers in Japan and China. While other Asian nations are digging deep into foreign-exchange reserves to mitigate the dollar’s damage, the yen and yuan’s slump is making things worse for everyone, threatening the region’s mantle as a preferred destination for risk investors.

“The renminbi and yen are big anchors and their weakness risks destabilizing currencies to trade and investments in Asia,” said Vishnu Varathan, head of economics and strategy at Mizuho Bank Ltd. in Singapore, using another name for China’s currency. “We’re already heading toward global financial crisis levels of stress in some aspects, then the next step would be the Asian financial crisis if losses deepen.”

The gravitational pull of Japan and China are evident in the sheer influence of their economies and trade relationships. China has been the largest trading partner of Southeast Asian nations for 13 straight years, according to a Chinese government statement. Japan, the world’s third-biggest economy, is a major exporter of capital and credit.

The tumble in the currencies of the region’s two largest economies may swell into a full-fledged crisis if it spooks overseas funds into pulling money out of Asia as a whole, leading to massive capital flight. Alternatively, the declines may set off a vicious cycle of competitive devaluations and a slide in demand and consumer confidence.

‘Bigger Threat’

“Currency risk is a bigger threat for Asian nations than interest rates,” said Taimur Baig, chief economist at DBS Group Ltd. in Singapore. “At the end of the day, all of Asia are exporters and we could see a reprise of 1997 or 1998 without the massive collateral damage.”

Beijing and Tokyo’s heft is even more pronounced in financial markets. The yuan makes up more than a quarter of the weighting of Asian currency indexes, according to analysis by BNY Mellon Investment Management. The yen is the third-most-traded global currency, so its weakness has had an outsized impact on its Asian counterparts.

The rising potential for spillover between the two largest regional currencies and their smaller peers can be seen in the fact they are moving in ever closer alignment as the dollar surges. The 120-day correlation between the yen and the MSCI EM Currency Index jumped to more than 0.9 last week, the highest since 2015, after the two were briefly inversely correlated as recently as April.

The threat of a spillover has become even more severe as currency declines accelerate. The yen tumbled passed 145 per dollar for the first time in more than two decades Thursday after US-Japan monetary policy divergence widened further when the Fed raised interest rates for a fifth straight meeting the day before. The yen retraced some of its losses after the authorities intervened but few see the action as doing anything other than slowing its inevitable decline.

The yuan slid past its own key level of 7 per dollar earlier this month, under pressure from the hawkish Fed and slowing growth in China caused by Covid-Zero lockdowns and a property-market crisis. The onshore currency extended losses on Friday to a level closest to the weak end of its allowed trading band since a shock currency devaluation in 2015.

Trigger Point

Specific levels such as the yen at 150 may bring on turmoil on the scale of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, according to market veteran Jim O’Neill, previously chief currency economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Others say the velocity of declines is more important than individual trigger points.

A rapid drop of the yen and yuan “can quickly become a ‘deadweight’ for other regional currencies,” said Aninda Mitra, head of Asia macro and investment strategy at BNY Mellon Investment Management in Singapore. “Much further yuan depreciation could be more troubling from here for the rest of the region.”

Of course, there’s no certainty further losses in the yen and yuan will bring on a financial upheaval. Nations in the region are in a far stronger position than they were in the run-up to the Asian financial crisis on the late 1990s, having greater foreign-exchange reserves and less exposure to dollar borrowing. Still, there are pockets of risk.

“The most vulnerable currencies are those with the deficit current-account positions such as the Korean won, Philippine peso, and to a lesser extent, the Thai baht,” said Trang Thuy Le, a strategist at Macquarie Capital Ltd. in Hong Kong. When the yen and yuan both fall, “the pressure can translate to dollar buying and hedging demand for those exposed to emerging-market currencies,” she said.