Beijing August 3 2022: China has made nearly $26 billion in short and medium-term loans to Pakistan and Sri Lanka over the past five years as its overseas lending shifts from funding infrastructure toward providing emergency relief.

Data showing the shift in China’s $900 billion Belt and Road Initiative to loans aimed at easing foreign currency shortages since 2018 was compiled by AidData, a research lab at William and Mary, a university in the US.

China has “pivoted in a significant way away from project lending and toward balance of payment lending, doing emergency rescue lending,” said Brad Parks, AidData’s executive director.

State-owned Chinese banks have lent $21.9 billion in short-term loans to Pakistan’s central bank since July 2018, while Sri Lanka received $3.8 billion of mostly medium-term lending since October 2018, according to figures compiled by AidData, based on official documents and media reports.

The loans show China is now playing a similar role to the International Monetary Fund, providing financing during balance of payments crises, rather than World Bank-style concessionary project financing to which BRI lending has generally been compared.

Higher US interest rates and energy prices are leading to foreign currency outflows from developing countries that are part of the BRI, increasing their risk of defaulting on foreign-currency debt. About 60% of China’s overseas lending is to countries that are now in debt distress, according to researchers at the World Bank.

The People’s Bank of China last year issued a $300 million emergency loan to bolster foreign exchange reserves of its neighbor Laos. Chile expanded a currency swap with China in 2020 to ease its economy through the pandemic, while Bank of China Ltd. the same year made a $200 million loan to the African Export-Import Bank for a pandemic relief program.

‘Weather the Storm’

“Beijing has been operating under the assumption that when BRI borrower countries face significant liquidity pressures, the smart move is to keep these countries sufficiently liquid to weather the storm,” Parks said.

The loans are “squarely focused on helping the borrower solve two problems: Number one, repay your old project debts, number two, to try to bolster foreign exchange reserves,” he added.

China’s emergency lending to Pakistan picked up when it started experiencing problems in balancing its international payments in 2017 as a result of surging import costs and overseas debt. The crisis prompted lengthy negotiations with the IMF, which demanded tax hikes as a condition for loans. About 27% of Pakistan’s foreign debt is owed to China, according to IMF data, incurred largely as a result of infrastructure projects.

Sri Lanka’s problems servicing foreign debt worsened as a result of the pandemic, when international tourism, a key source of foreign currency, collapsed and reached a crisis point this year as oil prices spiked. It has also been seeking IMF loans and pledged to slash government spending. About 10% of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt is owed to China, the government says.

China’s emergency loans tend to carry variable interest rates, rather than fixed ones as was typical with infrastructure lending, according to Parks. Maturities are much shorter than the 10-20 years typical for infrastructure loans.

Emergency lending to Pakistan generally carried maturities of 1-3 years and interest rates calculated according to prevailing interbank lending rates in London or Shanghai, plus a one to three percentage point margin, according to AidData.

The lending to Sri Lanka generally carried a maturity of around 10 years, a grace period of 3 years and interest rates calculated according to the LIBOR benchmark rate plus a margin of around 2.5 percentage points.

The loans to Pakistan and Sri Lanka came mainly from the PBOC in the form of currency swaps and loans from China Development Bank, Bank of China and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd., according to AidData.

The PBOC and central banks in Sri Lanka and Pakistan didn’t immediately respond to requests seeking comment. The Chinese banks and State Administration of Foreign Exchange also didn’t respond.

Countries with balance of payments issues are increasingly drawing on currency-swap arrangements with the PBOC, providing them with renminbi, which can also be sold for dollars.

While such deals boost countries’ foreign-currency reserves in the short run, “in net terms none of the fundamentals have changed, that money goes in and right back out,” said Parks. “If there’s a solvency problem rather than a liquidity problem you are potentially making things worse.”

China Swaps

China’s central bank has signed swap agreements with 40 countries and regions worth nearly 4 trillion yuan ($590 billion), according to an official report. Countries have turned to them during emergencies before, with Argentina drawing on a Chinese swap line in 2014.

Mongolia’s liability to China from the swap arrangement, which it started drawing on around a decade ago, has been extended several times and is now worth $1.8 billion, or 14% of Mongolia’s GDP, with a due date of 2023, according to the IMF’s most recent report on the country.

China has a record of doubling-down on lending to countries experiencing payment difficulties. When oil price declines made it difficult for Angola to repay debt to China in 2016, China stepped-up lending to the African nation to $19 billion in a single year rather than allow a major trading partner to default, according to a report by Boston University.

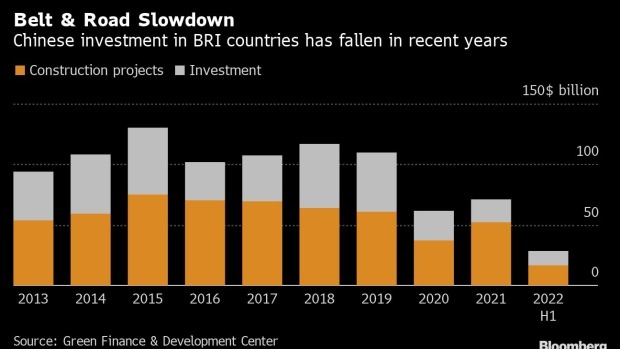

China’s BRI lending aims to allow China to earn returns from its more than $3 trillion of foreign exchange reserves, while filling a huge infrastructure deficit in developing countries. BRI lending has slowed sharply since 2017 for multiple reasons, including slower growth in China, lower commodity prices, a growing number of infrastructure projects facing difficulties and a domestic campaign against financial risks.

China’s total financial engagement since the BRI’s launch in 2013 is $931 billion, according to the Green Finance & Development Center, an affiliate of Fudan University in Shanghai. There was $28.4 billion in financing and investments for BRI projects in the first six months of this year, down 40% on the same period in 2019, it said. Sri Lanka received no new loans over the period.