Beijing September 15 2022: Six months after China’s government set ambitious economic targets for the year, growth has slowed so sharply that several major banks don’t even think 3% is achievable anymore.

Growth projections have come down steadily since March, when the official target of around 5.5% was first disclosed. The consensus in a Bloomberg survey is for the economy to expand 3.5% this year, which would be the second-weakest annual reading in more than four decades. Forecasters at Morgan Stanley and Barclays Plc are among those predicting even slower growth as risks mount into year-end.

It’s not just China’s strict Covid Zero policy of lockdowns and mass testing that’s buffeting the economy. A housing market collapse, drought, and weak demand both at home and overseas have all undercut growth.

Jian Chang, Barclays’s chief China economist, last week cut her full-year growth forecast to 2.6% from 3.1%, citing the “deeper and longer property contraction, intensified Covid lockdowns, and slowing external demand.” The cash crunch faced by developers will extend into 2023 and weak confidence in the real-estate market and the economy will hold back any meaningful recovery in home sales, she wrote.

Official data for August, due to be published on Friday, will likely show little improvement in industrial output, retail sales and investment. September’s figures don’t look any better either, with early indicators showing further contraction in the housing market and damage to consumer spending because of travel restrictions.

The People’s Bank of China refrained from taking any easing steps on Thursday, holding key policy interest rates steady on Thursday and draining liquidity from the banking system which is overflowing with cash. Further PBOC easing would put more pressure on the depreciating yuan and could increase capital outflows.

State media is striking a positive tone on the economy’s outlook. Growth is expected to rebound markedly in the current quarter compared to the previous three months, the China Securities Journal reported Thursday. The report cited early indicators and economists that pointed to recovering commodities demand and the easing of restrictions on production put in place after extreme temperatures.

However, the International Energy Agency is forecasting that oil demand in China will drop 2.7% this year, the first decline since 1990.

What Bloomberg Economics Says…

China’s recovery likely stalled in August, hit by heatwaves, power shortages and Covid-19 flare-ups — on top of a property slump. Leading indicators signal weakening momentum from output to consumption.

With the Communist Party gearing up for its twice-a-decade leadership congress in mid-October, Covid restrictions are being tightened and travel is being discouraged to avoid the spread of infections, throwing a pall over tourism spending during the nine-day National Day holiday break at the start of next month.

Here’s a look at the main risks the economy is facing and what the latest data and alternative indicators tell us about the outlook for the rest of the year.

Covid Zero

The biggest drag on the economy is the Covid Zero policy, which the government remains committed to despite more infectious virus strains making it harder than ever to control outbreaks. The virus has spread to every province this year and almost 865,000 people have been infected.

Major cities like Shanghai, Shenzhen and more recently Chengdu have locked down their populations and shut businesses to curb outbreaks. Frequent Covid testing is required — as often as every 48 hours in Beijing now — even in places where there are no outbreaks.

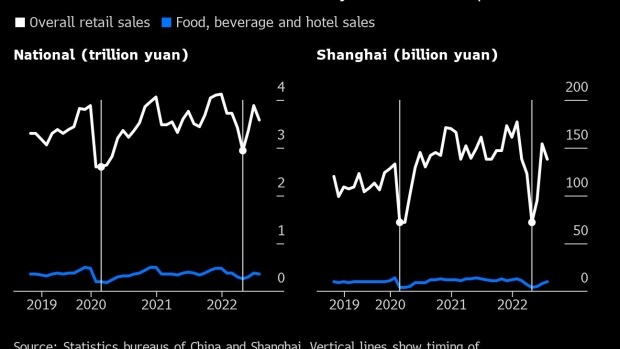

The restrictions have taken a toll on consumers, with spending taking months to recover after lockdowns. The official consumer confidence index plunged to its lowest level in nearly 10 years in April and it’s barely recovered since. Tourism has been decimated.

“The overall economic impact of Covid restrictions almost certainly worsened at the margin in August, and likely will again in September,” Ernan Cui, an analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics, wrote in a recent report. “The repeated high-profile lockdowns in major cities such as Shenzhen might remind households of the possibility of more disruptions to come, encouraging them to consume less and save more — as they have since the start of the pandemic.”

While some China watchers have speculated the Covid Zero policy may be eased after the Communist Party’s congress in October, economists at Nomura Holdings Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. say that’s unlikely. Nomura predicts the policy will remain in place until at least March next year. If it’s gradually eased from then, the economy could be in for a difficult period with people “overwhelmed by a surging Covid infection,” Lu Ting, Nomura’s chief China economist, wrote in a recent report.

Aside from the direct healthcare costs of a spike in illness and death, a widespread outbreak would also mean extended disruptions to business and consumer activity as people stay home to avoid getting infected and absenteesim from work rises.

Housing Crisis

What started in 2020 as an attempt by the government to cut the amount of risky debt held by property developers has developed into a crisis for the entire property market. Major builders have defaulted and halted construction, home owners have halted mortgage payments because of unbuilt homes, and demand for concrete, steel and everything else needed to build apartments have slumped.

There’s no sign that the contraction in homes sales — which began in July last year — has eased. The almost 900 billion yuan ($129 billion) of homes sold in July this year was about 30% below the amount sold a year earlier. Sales declined at the same speed in every week in August and preliminary data for September showed the trend continuing.

About 660 million square meters of homes were sold this year through the end of July, the lowest amount since 2015.

The crisis has undermined the wealth of Chinese households, who keep much of their wealth in real estate. Prices for new homes have contracted for 11 consecutive months, with the deepest declines happening in the smaller and regional cities where the majority of people live.

Slowing Factories

The housing crisis is rippling across China’s critical manufacturing sector. Steel output dropped to a four-year low in July, and even though there are some signs of a recovery, demand remains very weak, with inventories 41% higher at the end of August than they were at the start of this year. Meanwhile, cement output over the past year was the lowest it’s been in more than a decade.

While that has been good for reducing China’s carbon emissions, it’s not good for the manufacturing sector, which contracted for a second month in August, according to purchasing managers surveys.

Global demand for Chinese-made goods is also slowing after a two-and-a-half year boom in exports, another drag on manufacturing. Even though the value of exports still rose 7.1% in August from a year earlier, volumes are under pressure. Shanghai port, the world’s largest, processed 8.4% less cargo by weight in August compared to a year earlier.

On top of that, China just had its hottest summer on record, with the drought and heat causing power shortages in some areas, curbing output in July and August, and damaging crops. The full extent of the damage will take months to become clear, although autumn harvests will likely be affected and power shortages could persist, especially for heavy users like aluminum smelters.

Worsening Fiscal Situation

Local governments are spending more on Covid testing and quarantine — with that cost likely to rise for the rest of the year as restrictions are tightened. At the same time, their revenues are plummeting because of a slump in land sales and tax cuts.

Budget shortfalls have soared: the augmented deficit was 5.25 trillion yuan in the year through July, almost the same as for the whole of 2021 and worse than at the same point in 2020. Some governments can’t pay their their bills on time, with Bloomberg calculations showing Covid testing companies are struggling to get paid.

Local governments sold a record amount of so-called special bonds in the first half of the year, but those funds are mainly for infrastructure investment, not general expenditure. Even though infrastructure spending is being ramped up, economists say it won’t be sufficient to compensate for the slump in property investment, and the government may need to boost borrowing in the rest of the year to plug the budget gap.