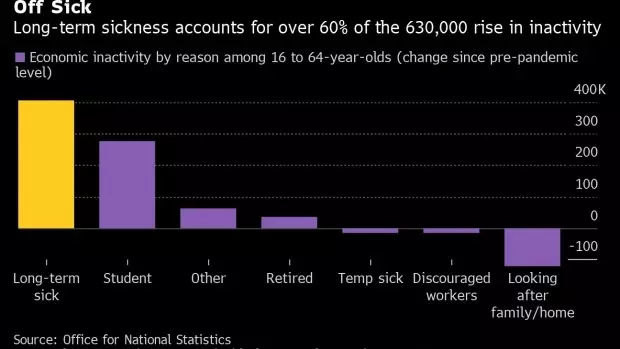

London December 29 2022: Mental health issues are keeping Britain’s workers out of work at record levels at a time when the economy needs them the most.

Amid a bleak economic outlook, falling real wages and a creaking National Health Service, there’s mounting evidence that the country’s young working age people are suffering from long-term health issues that are keeping them out of work at increasingly alarming rates.

There was a 29% increase in 16-24 year-olds citing long-term sickness as a reason for being economically inactive and a 42% jump among people aged 25-34 who said the same, according to the Office for National Statistics. That data is for the second quarter of 2022 when compared to the same period before the pandemic.

It’s not just young people, either. Work-related stress was reported as the biggest driver of inactivity among 50-54 year-olds, according to government data. Overall, mental health issues account for a total of around 600,000 economically inactive people across all age groups, according to ONS data, a 10% increase on pre-pandemic figures.

Given the strong correlation between mental health disorders and worklessness, a rise among Britain’s youth has direct economic consequences. It’s feeding salary competition between firms, adding to pressures on inflation that’s already near a four-decade high.

The data also point more generally to a worrying decline in the health of the nation, with the youngest workers facing a recession and wages that fail to keep up with double-digit inflation.

Chronic Problems

This is not just a post-pandemic phenomenon — industry experts say it’s been building over the past decade. Louise Murphy, economist at the Resolution Foundation said health among the younger generation was already deteriorating “quite dramatically” before the pandemic. But the issue has become more acute since Covid.

“There’s no doubt that Covid has accelerated the mental health problems in this age group,” said Majorie Wallace, chief executive officer of the mental health charity Sane. “They’ve been out of schools, potentially exposed to fractious domestic atmospheres at home, and spent more time on social media.”

NHS Digital data showed that one-in-four 17-19 year-olds in England had a probable mental disorder in 2022, up from one-in-six in the previous year.

This adds to recent research from the Institute for Public Policy Research that showed that mental health problems were the most common conditions among those out of the workforce due to long-term sickness. The report from December also said that 20-29 year-olds not working because of illness were 50% more likely to report a mental health problem than older working-age adults.

The problem is particularly pronounced among men, according to the Resolution Foundation. The number of inactive males with mental health issues increased to 37,000 in 2021, a 103% increase on 2006 figures, and substantially higher than levels seen among women.

“The reason that (deteriorating health) hasn’t been a big story in recent years is that it was this almost exactly outweighed by fewer young women being inactive to look after families,” said Murphy. “But when you split it up by type of inactivity, it’s quite clear.”

Why Now?

Both the ONS and the IPPR point towards an overworked and under-performing NHS as a key factor in the nation becoming sicker, including with mental health disorders, adding that longer waiting times since the pandemic have likely exacerbated the problem.

Figures from Imperial College London show that the number of GP appointments attended by people aged between 15-24 years declined by 31% during the first Covid lockdown in 2020 when compared with previous years. That may indicate a potential increase in undiagnosed problems.

“It is no surprise to see population mental health in crisis,” said Chris Thomas, head of the commission on health and prosperity at the IPPR. “Access to services steadily worsened during austerity. And a combination of Covid-19 and the cost-of-living crisis are taking a huge toll. We face nothing short of a mental health recession.”

Wallace added that mental health has been neglected in the UK, leading to a system ill-equipped to cope with the “rising tide” of young people over the past decade.

“There’s been a decimation in psychiatric beds — we’ve lost 60,000 over the past 30 years,” she said. “Many people now have to rely on community care, which has been shown to be less effective given their teams are often so threadbare.”

Of course, causal factors are also at play. Social media’s role in driving mental health issues among young adults has been well-documented, with Wallace adding that it likely plays the largest part in the deteriorating picture among the younger generation.

But data suggest that mental health has socio-economic links too. NHS Digital reported that that children in homes experiencing financial strain were particularly susceptible to anxiety and stress, indicating that amid one of the worst squeezes on household incomes in memory, the problem could worsen.

“The general climate at the moment with the cost of living crisis, conflict in Ukraine, political uncertainty — all of that is quite destabilizing for a young person,” said Josh Knight, senior policy officer at Youth Employment UK.