New York July 24 2022: The pandemic has put unprecedented strain on global supply chains -– and also on the workers who’ve kept those systems running under tough conditions. It looks like many of them have had enough.

A surge in strikes and other labor protests is threatening industries all over the world, and especially the ones that involve moving goods, people and energy around. From railway and port workers in the US to natural-gas fields in Australia and truck drivers in Peru, employees are demanding a better deal as inflation eats into their wages.

Precisely because their work is so crucial to the world economy right now –- with supply chains still fragile and job markets tight –- those workers have leverage at the bargaining table. Any disruptions caused by labor disputes could add to the shortages and soaring prices that threaten to trigger recessions.

That is emboldening employees in transportation and logistics -– which spans everything from warehouses to trucking — to stand up to their bosses, according to Katy Fox-Hodess, a lecturer in employment relations at Sheffield University Management School in the UK. She points to already-tough working conditions in the industry after years of deregulation.

Workers Bear Brunt

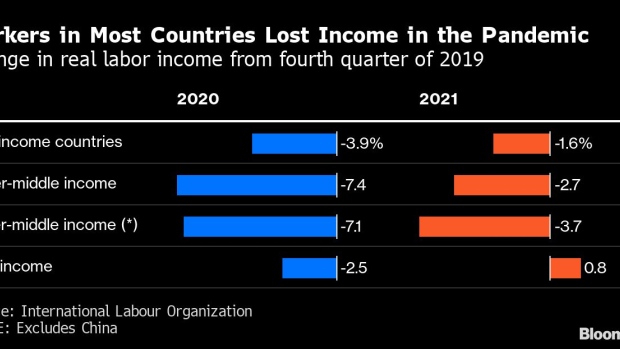

“Global supply chains weren’t calibrated to deal with a crisis like the pandemic, and employers have really pushed that crisis onto the backs of workers,” Fox-Hodess says.

For their part, central bankers have been fretting about workers getting paid too much and setting off a wage-price spiral like the one that sent inflation soaring in the 1970s. In fact there’s not much sign of that, with wage gains generally lagging behind prices, partly because organized labor is broadly less powerful than it was back then.

But that may mask a different problem. Much of today’s inflation stems from specific chokepoints -– and labor unrest in those key industries could have wider ripple effects on prices. A threatened strike by Norway’s energy workers, for example, sent fresh tremors through European natural-gas markets earlier this month.

There’s also a risk to the rebalancing of economies. In the pandemic, people bought more goods at the expense of services like plane tickets or hotel rooms, putting pressure on supply chains and stoking inflation. The expectation is that spending habits will revert to normal, with consumers eager to take a trip again. But strikes by cabin staff at Ryanair Holdings Plc, or airport workers in Paris and London, are adding to the travel turmoil that may put would-be tourists off.

Here’s a roundup of some of the hot spots of labor unrest rattling the global economy.

Trains and Trucks…

In the US, where a long-declining labor movement is showing signs of awakening as unions establish footholds at companies like Starbucks Corp. and Amazon.com Inc., some of the biggest disputes are in the transportation industry. Looming over the country’s already battered supply chains is the threat of a rail strike that could paralyze the movement of goods.

After two years of unsuccessful negotiations with the nation’s largest railways, President Joe Biden this month established a panel to resolve a deep rift between 115,000 workers and their employers. The Presidential Emergency Board has until mid-August to come up with a contract plan that’s acceptable to both sides.

“There’s a very tight labor market, so that puts workers in a position where they have both an accumulation of lots of grievances and they feel empowered,” Cornell University associate professor Eli Friedman said. The school tracked 260 strikes and five lockouts in the US involving about 140,000 employees in 2021, leading to about 3.27 million strike days.

In the UK, train drivers say they will strike on July 30, and two other transportation unions are also planning 24-hour walkouts next week. It’s not just passengers who will suffer: A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S, the world’s No. 2 container shipping line, warned that those actions would cause “significant disruption” to the movement of freight.

Canada has seen strikes on its railways, too — part of the country’s biggest wave of labor strife for decades. Tens of thousands of construction workers also walked off the job earlier this summer. In May, there were 1.1 million worker-days lost to stoppages, the highest monthly total since November 1997.

In many countries, truck drivers protesting against the high cost of fuel have been at the forefront of labor unrest. Truckers in Peru are holding a nationwide strike this month. In Argentina, roadblocks by drivers in June lasted a week, delaying about 350,000 tons of crops -– roughly 10 small ship cargoes. In South Africa, drivers blocked roads including a key trade link to neighboring Mozambique, in a demonstration against record pump prices.

…And Ports and Ships

The labor dispute that US economy watchers worry about most is the one involving more than 22,000 dockworkers on the West Coast. Their contract expired at the start of July, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union is negotiating a new one. Both sides say they want to avoid stoppages that could shut down ports handling almost half of America’s imports.

Meanwhile the Port of Oakland, California’s third-busiest, had to close some of its gates and terminals this past week -– adding to the wait time for imported goods — because truckers blocked access in protest against a gig-work law that could take 70,000 drivers off the road.

German ports are scrambling after a two-day strike earlier this month worsened cargo bottlenecks that are snarling shipping and hurting Europe’s largest economy.

In South Korea, the shipbuilding industry has seen a surge in orders amid the supply-chain crunch. Workers have been protesting for several weeks at a dock for Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co. in the southern city of Geoje, demanding a 30% pay hike and an easing of their workload. The action has already delayed the production and launch of three ships, and President Yoon Suk Yeol urged ministers to resolve it. A resolution looked to be close as of this weekend.

Air-Travel Chaos

Labor disputes have contributed to Europe’s summer of travel chaos, with air and rail companies already short-staffed after the pandemic squeeze on labor markets. Carriers including Ryanair, EasyJet Plc and Scandinavia’s SAS have seen their schedules disrupted by strikes.

A walkout at Charles de Gaulle Airport outside Paris forced the cancellation of flights, and London’s Heathrow looked at risk of a similar fate before the Unite Union called off a proposed walkout on Thursday, saying it had received a “sustainably improved offer” of pay raises.

Even in normally relaxed Jamaica, flight controllers staged a one-day strike on May 12 to complain about low pay and long hours, closing Jamaican airspace and disrupting travel for more than 10,000 people in the Caribbean island. At least one plane was forced to return to Canada mid-trip.

Energy Crunch

A strike by oil workers in Norway threatened another blow to Europe’s energy supplies, which have already been hit by the war in Ukraine with reduced gas flows from Russia. The dispute was resolved when the government stepped in to propose a compulsory wage board. The country’s labor minister said she had no choice but to intervene, because of the potential for “far-reaching societal impacts for all of Europe.” A further escalation of the strike could have shut down more than half of Norway’s gas exports.

In Australia, one of the world’s top exporters of liquefied natural gas, workers on Shell Plc’s Prelude floating LNG production facility in Western Australia have extended industrial action until Aug. 4, according to the Offshore Alliance union. The stoppage has halted loading at an export facility, exacerbating global shortages of the fuel.

Labor groups at South African state-owned utility Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd. won a pay increase that roughly keeps pace with inflation after a weeklong walkout that worsened the country’s power outages — and was illegal under laws that bar Eskom workers from striking because the provision of electricity is considered an essential service